#MUACenlaCiudad: Andy Medina

Who’s the Illiterate Now? questions the relationship between language, power and identity. Through an experience of alienation in the codes of public space, this piece reflects on the role of language not only as an instrument of power, but as a key piece of racial and linguistic hegemony.

An Act of Speech

Who’s the Illiterate Now? exposes the violent role played by the public education system in the racial and linguistic unification of the Mexican state. This project transformed a pluriethnic society in which the many languages in use overlapped into an apparently monolingual nation, crossed through with a multitude of linguistic hierarchies. The educational program of the Mexican state, camouflaged by indigenist ideologies, sought the systematic eradication of indigenous languages as part of the project to transform the mosaic of cultures that inhabited the territory into a “mestizo” society, that is, a castellanized and westernized population, falsely described as being the product of cultural and biological hybridization. The legacy of this project has not only been the endangerment of the majority of the languages of indigenous nations, but also an ideology that has established a cultural equivalence between “the ignorant” and “non-Spanish-speakers.” This equivalence is wrapped in centuries-old layers of racist, Eurocentric violence that continue to be translated into a structure of legal inequality, in which a large part of the population lacks access to the basic rights of citizenship by not being Spanish speakers or for giving away, through their personal usage of the colonial language, their differentiated genealogy.

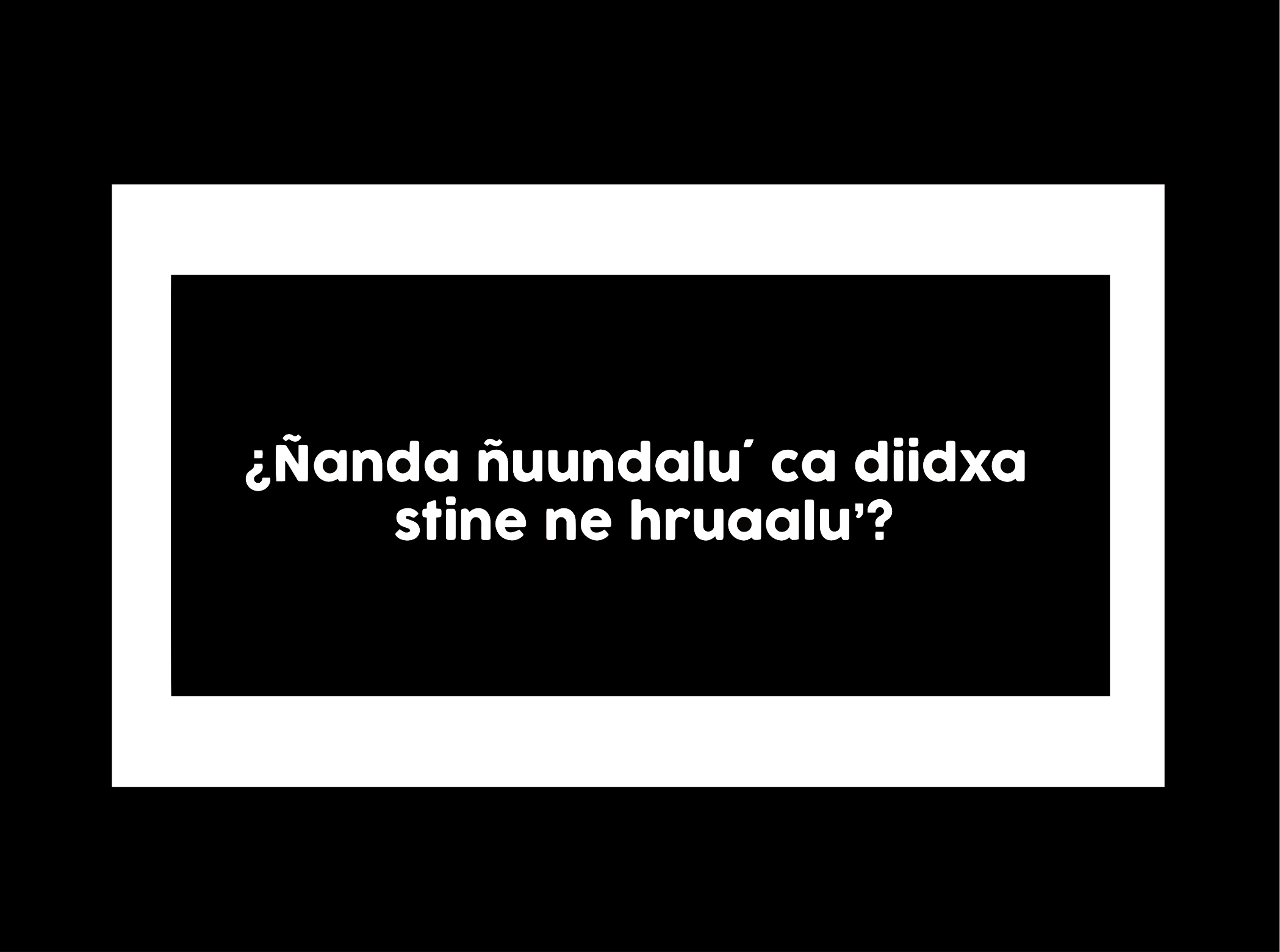

The project that Andy Medina presents for #MUACenlaCiudad, which has been in development for several years, seeks to undo the ideological equivalence between culture and Hispanicness. With the goal of subverting the meaning of language politics, Medina has produced posters in Mixe from Tlahuitoltepec, Zapotec from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and Mixtec from Oaxaca, with the phrases “Who’s the illiterate now?” and “You don’t know” which will be placed all over the city. Whoever walks down the streets of Mexico City, the seat of national power and federal linguistic policy, will read these words in a language that will likely be foreign to them—unless they speak one themselves. With this piece, Medina seeks to transpose towards the urban majority the experiences of alienation and confusion lived by thousands of speakers of non-Western languages when arriving to the big cities. The artist’s purpose is to invert, at least momentarily, the sense of colonial linguistic hegemony: those accustomed to considering themselves legitimate interlocutors are forced to undertake a translation act for which they lack the tools. In a secondary moment of access, the piece becomes an act of speech when the spectators read the title that translates the phrase into Spanish and, hopefully, put themselves in the place of the illiterate.

As Judith Butler has stated, “Language sustains the body…it is by being interpellated within the terms of language that a certain social existence of the body first becomes possible.”1 That is, the social body becomes accessible and appears at the moment in which it is interpellated. Thus the importance of this enunciation act as a space in which a community is constituted and positions itself.

In his piece, Medina recognizes the place of resistance that language has represented for many communities who protect their culture and way of life through the daily practice of enunciating them in their indigenous languages. According to the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI), there are 68 indigenous languages in Mexico, but most of them are vulnerable: according to official data, 31 are at “high risk” of disappearing and 37 are “threatened.”2

According to the currents of the Linguistic Turn, led by Richard Rorty, language not only operates as a means of understanding reality, but as a constitutive part of it, an agent that creates worlds.3

The linguistic alienation created by this piece reveals the annulment of certain subjects in a social system that denies them the possibility of “being” and “forming part of” the community. Words and phrases are not conceived as a mere communicative tool, as they constitute an oppressive epistemic-ontological apparatus.

In the context of 500th anniversary of the Conquest and the imposition of the Spanish language in Mexico, it is time to rethink and safeguard the role of the country’s indigenous languages, recognizing this task as a responsibility we all share, not just those who speak them.

Who’s the Illiterate Now? makes clear that language is a double-edged sword, one that can either subject and exclude a community or be a refuge, echoing Judith Butler’s question: “What if language has within it its own possibilities for violence and for world-shattering?”4

Alejandra Labastida and Virginia Roy

[1] Judith Butler, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative, New York, Routledge, 1997, p. 5.

[2] https://www.gob.mx/cultura/articulos/lenguas-indigenas?idiom=es.

[3] Richard Rorty, El giro lingüístico, Barcelona, Paidós, 1990.

[4] Ibid., p. 6