Sala10: Francis Alÿs

Playing Among the Ruins

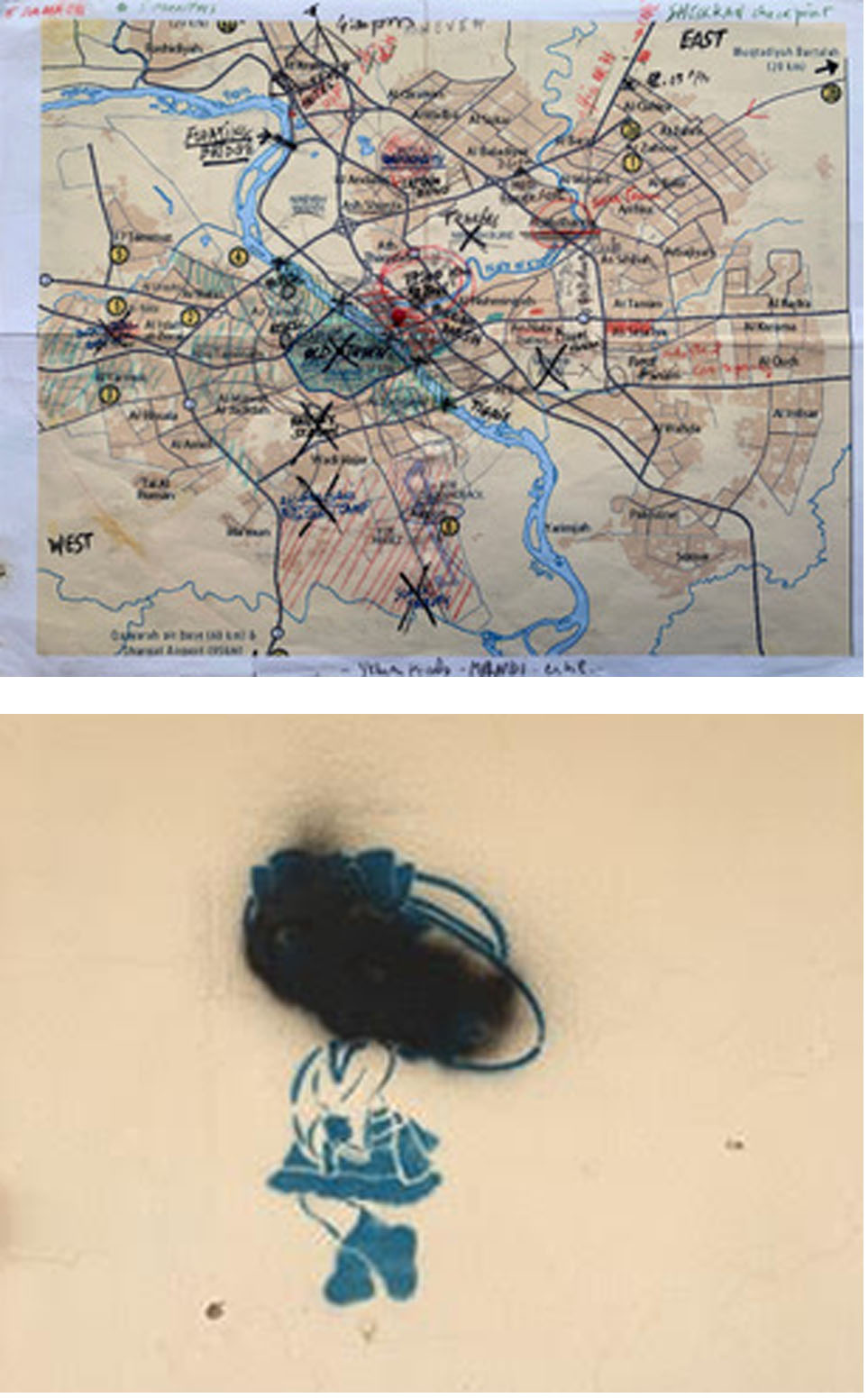

In August 2017, during the final phase of the Fatah (Conquest) Operation, the Iraqi Army pushed Islamic State combatants back from the east bank of the Tigris River in Mosul. With the support of Baghdad’s Ruya Foundation, Francis Alÿs had been working with the inhabitants of the border region between Iraq and Syria, embedded with the armed forces fighting the Islamist militias.

On the west bank of the Tigris, which had just been liberated from Daesh control, Alÿs documented a peculiar street game that he had heard of on a previous trip: a soccer game played without a ball, but with great skill, imagination and resistance by a group of young people, in defiance of the barbarous impositions of the Islamic State, an expression of passion and creativity that these young people were more than willing to reenact in front of the camera.

The conditions under which this game arose are complex. The Islamic State declared many things to be haram (forbidden) in the territories it occupied, such as beauty parlors, drawings of human figures, all books besides the Quran, certain pets and games of chance. The Islamists also sought to eradicate soccer given its triple role as a sport, a passion and a spectacle. The reasons for this prohibition were many: the nakedness of the players’ legs contradicted traditional modesty, for example, and supporting teams and players could constitute idolatry, which violated the principle of exclusively worshipping Allah, one of the precepts of Islam that ISIS interpreted in a radical, brutal form. Certainly, the jihadists took to an extreme that suspicion that many Muslims in the Middle East feel towards soccer, which, as a Western sport, is seen as somewhat degenerate.

Daesh energetically attempted to impose this prohibition. In January 2015, the Western press reported one particularly horrific incident: a group of 13 children in Mosul were executed by Islamists before a crowd that included their parents for allegedly having been caught watching the Iraq-Jordan match in the Asian Cup.1

Alÿs shot this video in two half-hour takes, but on the second day, the game was interrupted by the sound of gunfire, which immediately caused the players to disperse.

The Iraqi colonel who had taken him to that street, which contained the ruins of the radio station run by foreign jihadists, recommended that he retreat and dissuaded him from returning. Curiously, this dematerialized game allowed Alÿs to include soccer in his series Children’s Games. The prohibition forced Mosul’s adolescents to reduce the sport to one practically free of accessories, defined by a self-regulation that requires no explicit rules. 2

This “forbidden soccer” is a particularly extreme case from a series of short videos that aspire to be an archive of the ways in which children from around the world use play as a shared social narrative, among its other functions, because the tenacity of its practitioners resists the uniformity of capitalist rationalization, as well as the political program of Islamic extremism. This challenge is expressed in the pride with which these players wear the jerseys of their favorite teams, even though they were to disfigure their names and logos to please the iconoclasts.

This piece is one of the most moving by Alÿs, as it captures the depth and tenacity of play, but also the importance of a connection with the world for those who live in times of tragedy. Seeing these images reminds us of the dignity conferred by facing danger and defending one’s dreams.

Cuauhtémoc Medina

March 2020, at the threshold of pandemia

Francis Alÿs, Children’s Games #19: Haram Soccer

Mosul, Iraq, August 2017

Color, video, 9’11’’

Thanks to Baghdad’s Ruya Foundation and the children of Mosul

Foot notes:

[1] See Quentin Miller, “How Football Survives on Islamic State’s Turf,“ Vice, August 21, 2018 [Originally published by Vice France]. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en_asia/article/d7mp8x/how-football-survives-on-islamic-states-turf. This article served as a basis for Alÿs’s research and was recommended to the author by the artist.

[2] On the series Children’s Games, see: Francis Alÿs, Children’s Games, Marente Bloemheuvel and Jaap Guldemond (eds.), Amsterdam, Eye Filmuseum, 2019, which includes my article: Cuauhtémoc Medina, “A Collection of ‘Innumerable Little Allegories’ - Francis Alÿs’s Children’s Games,” pp. 14-23. Many videos in the Children’s Games series are freely available at the artist’s website: http://francisalys.com/category/childrens-games/

Francis Alÿs

(Born 1959, Belgium; lives and works in Mexico City)

Trained as an architect and urbanist, Francis Alÿs moved to Mexico in 1986 to work with local NGOs. Circa 1990, he entered the field of visual arts. His practice embraces multiple medias, from painting and drawing to performance and video. Although his studio is based in Mexico City, he has produced over the last 20 years numerous projects in collaboration with local communities around the world, from South America to North Africa and Middle East. In Peru he produced an event where 500 volunteers moved a sand dune just a few centimeters (When Faith Moves Mountains, Lima, 2002). Since February 2016, he has been engaged in a series of projects in Iraq, such as Color Matching; filmed while being embedded with a Peshmerga Battalion during the siege of Mosul. His latest is the feature film Sandlines (2018-19) in which the children of a small mountain village near Mosul re-enact a century of Iraqi History.

#Sala10

The nine galleries in the MUAC's University Cultural Center building are now joined by #Sala10, the museum's dematerialized tenth gallery. This gallery will be a biweekly virtual exhibition space with contemporary art content that can be accessed on the MUAC website in a variety of digital formats. #Sala10 understands contemporary art as being an expression of sensitivity, thought, critique, poetry, foresight, beauty, conflict and energy that lies latent in the playback capabilities of our electronic devices.