Sala10: Minia Biabiany

virtual exhibition

Musa

Minia Biabiany explores the colonial violence produced in her country, Guadeloupe, a French possession in the Caribbean, as she explores the history of her family through the women of her line. Using metaphors involving traditional tools, the country's landscape and nature, Musa evokes and recalls the history of oppression that has endured in their corporeal unconscious.

Skin of Memory

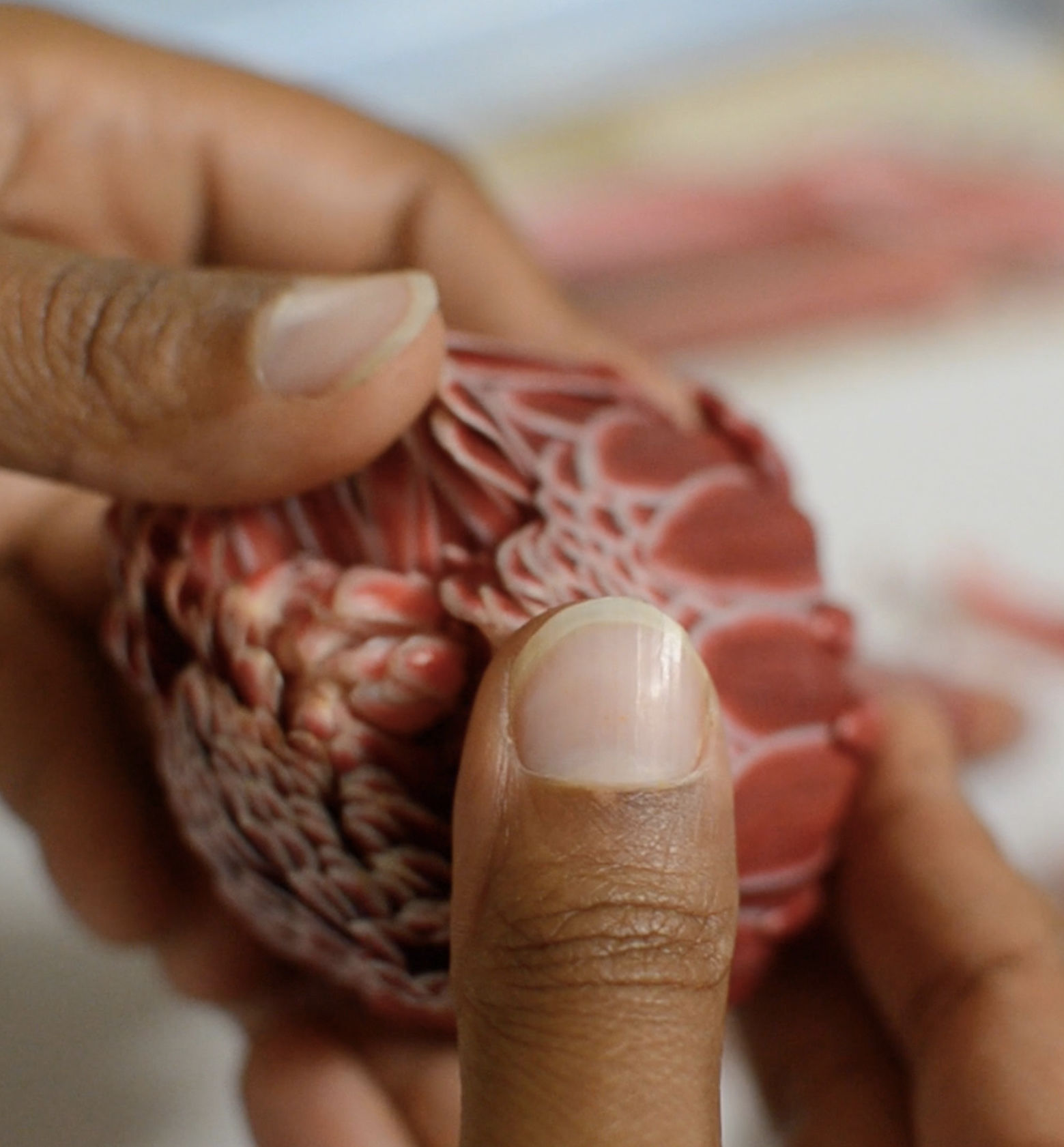

Musa paradisiaca is the scientific name of the banana plant that grows in warm latitudes of Asia and the Americas. Its flower, with its attractive purples and reds, is a habitual element in different autochthonic cuisines and is also used for medicinal purposes, in particular for pelvic pain. This flower forms the backbone of this piece, which explores notions of colonialism and territorial identity. The artist emphasizes its curative properties given her country’s circumstances, in which nearly 90% of the land is contaminated by the pesticide chlordecone, which was used by France in the seventies and eighties, and which has provoked health problems in people’s sexual organs and in child development.

Biabiany thus addresses the way in which the colonial wound penetrates the memory of her family and festers on the place’s skin, like the banana plant. Its petals open up, blossom, ripen and fall, in a cycle that alludes to the island’s submission and slavery. The flower’s fragility contrasts with the violence of the history of slavery and the tension with which the place is inscribed with the memory of sexualized and exoticized bodies. Presented as a body, the flower symbolizes the history and also the lineage of a territory. In the artist’s own words, “The writing of the territory contains that of my body.”[1]

The presence of the female body is observed, in turn, in the images of bellies like umbilical cords that tie us to genealogical lines and female sexuality. Bodies are deployed here as if they were the island’s guts. The constellation of her family’s women reflects the rootedness of colonialism in a chain or thread of blood that subtly weaves that “movement that recalls” history through gestural repetition.

The allusion to food is also significant. Just as with the plundering of the territory, the leaf is chopped up and broken down, cooked and then swallowed. The plant is presented as an organ, a phagocytic tongue that is devoured but also devours, just as it has devoured the island’s culture, history and land.

Threads occupy an important place in Biabiany’s production, both physically and conceptually. In this piece, the artist ties, knots and strings petals together, just as she ties and binds histories and memories. She thus creates a weave of textures and tales that submerges us in spaces of exploration in which the artist invites us to “unlearn seeing.”[2]

In Musa, the tongue appears as an organ but also as language. As in her other pieces, the video includes fragments of Antillean creole, both written and spoken. The sequence of pauses, as well as the softness of its sonority and orality, create a sense of intimacy. Creole is born from oral communication among enslaved peoples; language is political and creole dwells in that dispute.

Musa is thus a visual poem in which the poetics of images and words intertwine in order to demand that we listen: a whisper that comes to unravel the internalized and assimilated colonialism within us. As if undoing a tangle of threads, the piece unties histories. Musa speaks from the skin and the land, from the rain that permeates the sand and is absorbed by it, from the whisper of a past in tension.

It thus allows the presence of other tales to blossom, but above all, it suggests a space of memory. As Grada Kilomba argues, “The colonial past is ‘memorized’ in the sense that it was ‘not forgotten.’ Sometimes one would prefer not to remember, but one is actually not able to forget. Freud’s theory of memory is in reality a theory of forgetting. It assumes that all experiences, or at least all significant experiences, are recorded, but that some cease to be available to the consciousness as a result of repression and to diminish anxiety; others, however, as a result of trauma, remain overwhelming present. One cannot simply forget and one cannot avoid remembering.”[3]

[1] Minia Biabiany: ritmo volcán, México, Temblores Publicaciones, 2022, p. 114.

[2] Ibid., p. 98.

[3] Grada Kilomba, Plantations Memories, Berlin, Unrast, 2010, p. 132.

The Muscle and the Fruit

Eva Barois De Caevel

I wrote my first (and last, until now) text on the work of Minia Biabiany a little more than a year ago—before COVID, before everything that we know. It was a tense time; there had been great fires, the strike, confrontations, and crackdowns. Minia was in Grenoble for the opening of her exhibition j’ai tué le papillon dans mon oreille [I killed the butterfly in my ear].

Published in:

Minia Biabiany: ritmo volcán, Mexico, Temblores Publicaciones, 2022.

COMPLETE TEXT HERE

Minia Biabiany, Musa, 2020

Video, 14’

This piece is exhibited in collaboration with BIENALSUR

Minia Biabiany (1988, Guadeloupe, French West Indies)

The work of Minia Biabiany is built on the observation of a place through historical and phenomenological perspectives. Space is understood as a weave of relationships that arise through the gaze of the spectator, who wanders through an array of all kinds of elements (threads, natural fragments, photographs, writings, videos, poems). This formal language constitutes a poetics of a fragile, ephemeral place: in Biabiany's work, weaving—the creation of a surface through strings or threads—becomes a paradigm to understand our relationship with language. Whether oral, written or visual, her work uses languages to reconstruct narratives and imaginaries for reflection and healing in colonial contexts.

Curatorship: Virginia Roy Luzarraga

Texts: Virginia Roy Luzarraga, Eva Barois De Caevel

Content Direction: Ekaterina Álvarez Romero, Cuauhtémoc Medina

Curatorial Coordination: Ana Sampietro Brosa

Digital Management: Ana Cristina Sol Sañudo

Content Editing: Roberto Barajas Amieva, Vanessa López García, Yerem Mújica Toscano

English Translation: Julianna Neuhouser