Sala10: Edgardo Aragón

virtual exhibition

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect

This work presents a parallelism between the original destruction of Mesoamerican civilization and the current impact of private companies on communities in southeastern Mexico under the Mesoamerican Integration and Development Plan, an ambitious plan for developing electrical and transportation infrastructure. Edgardo Aragón centers his work on a specific geographical point: the town of Cachimbo, on the state line between Oaxaca and Chiapas. This community is constantly battered by hurricanes and has to be rebuilt each year, without government help or even electricity.

Cachimbo: Sea and Wind

The term Mesoamerica (Middle America) was coined in 1943 by the German historian and ethnologist Paul Kirchhoff to describe a geographical and cultural area that includes what is now the southern half of Mexico, the countries of Guatemala, Belize and El Salvador and the Pacific coasts of Costa Rica and Honduras. This area is one of the most biodiverse in the world and, for Kirchhoff, its ancient civilizations shared cultural, religious and civilizational traits that allow them to be grouped together as an identifiable cultural region.

In 2008, the so-called Mesoamerica Project was launched. Designed as an aid and investment plan for the region’s infrastructure, its stated goal was to reduce social inequality and poverty and to create educational and development opportunities. Nevertheless, later studies have shown that the plan became a strategy by private companies to exploit the region’s natural resources and that it has not functioned to promote industrialization and technology transfer.[1]

In Oaxaca in particular, private companies built wind farms on land that was, at the time, communally owned, but was privatized in 1992. To date, these wind farms have not provided nearby communities with electricity.

Edgardo Aragón’s artistic production utilizes the specific context of Oaxaca to address broader problems and concerns: drug trafficking, immigration, land struggles, the disappeared, the abuses of the neoliberal economy, privilege and a long etc., the elements that constitute the society of confrontation and dissent we inhabit.

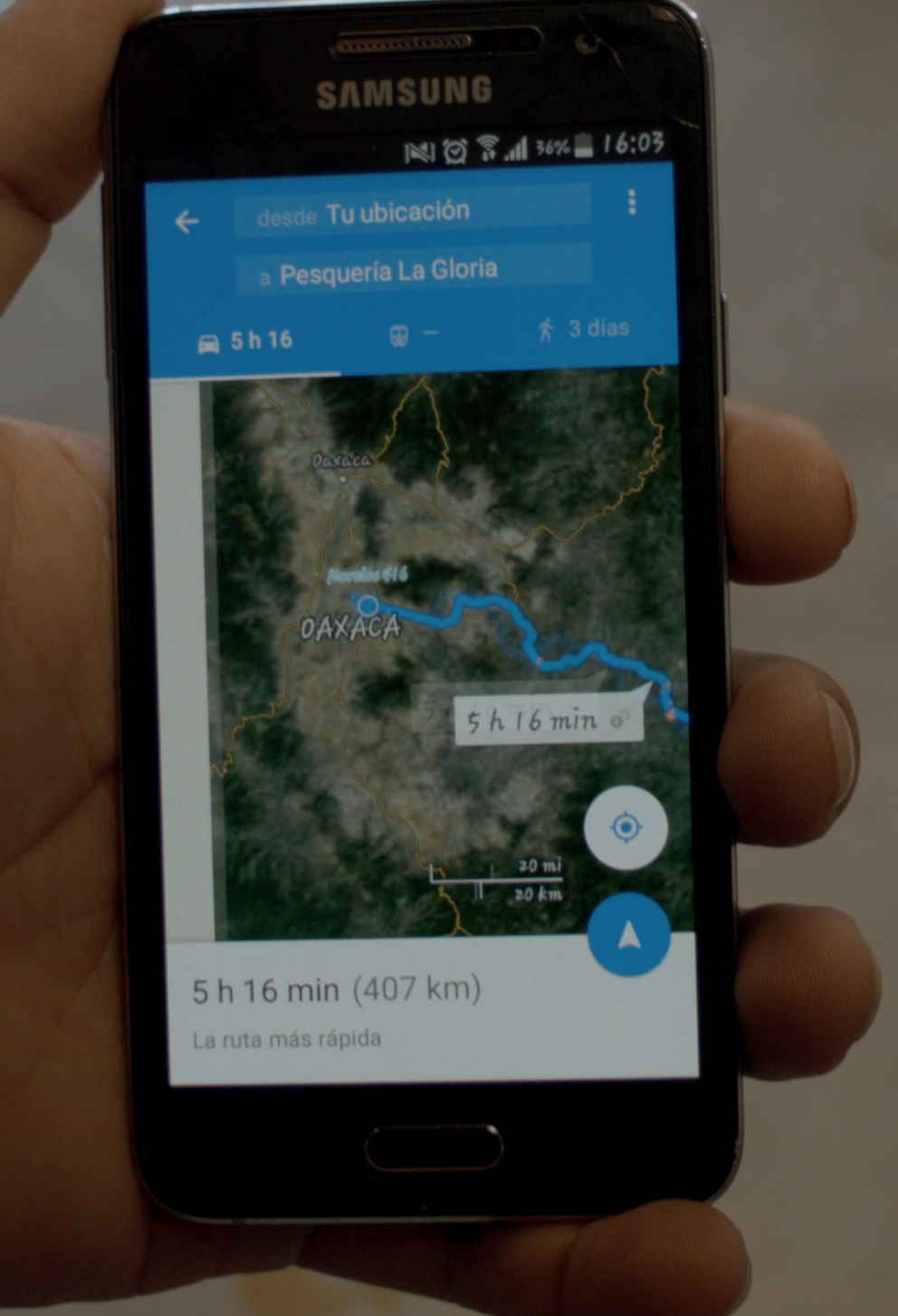

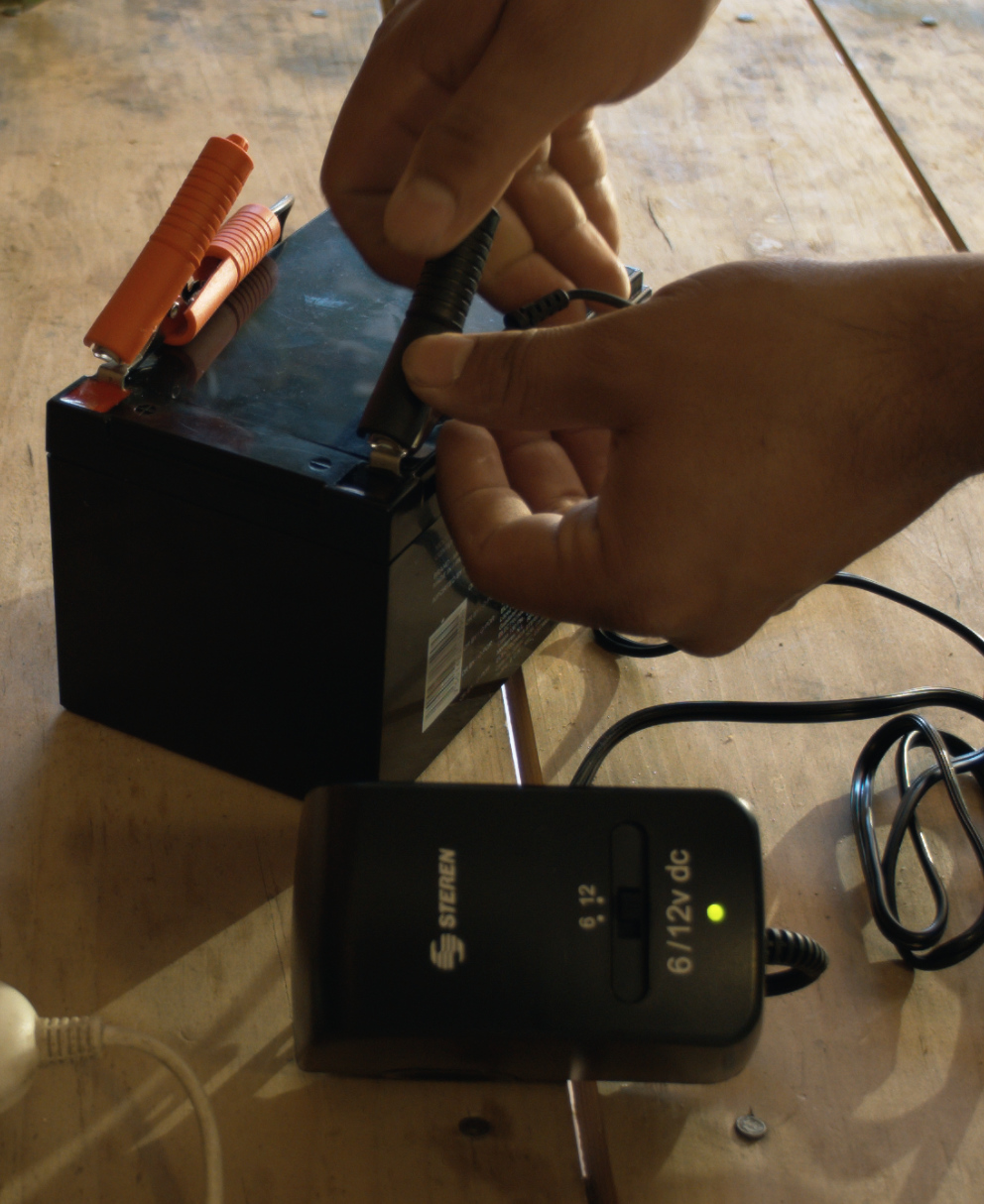

In Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, Aragón explores the region’s energy conflict. As wind farms spread across Oaxaca, the Huave people of Cachimbo, located just eight kilometers from one, fight against the fragility of their infrastructure on a daily basis. Aragón filmed here in the wake of Hurricane Barbara, which left the town underwater. Tropical Storm Boris finished off what was left. The precarity of life in Cachimbo made reconstruction difficult. With this piece, Aragón captures a paradox: although the town is surrounded by wind farms, it lacks electricity. To make this contradiction visible, the video follows someone bringing a source of electricity to Cachimbo.

Aragón’s work is characterized by its use of the landscape as a metaphor for the territory. The landscape is understood as an expanse that is contemplated for its visual and spatial qualities, and which serves as a symbol of its political administration. The arid environment of Oaxaca is presented as a reflection and representation of the hidden systemic violence that underlies the region’s political disputes. For Aragón, the importance of place and a connection with the land are manifested by the constant presence of geography in his work. By filming the landscape, Aragón introduces us to the struggle and resistance of the Cachimbo community. This small town is also home to sea turtle poachers and smugglers of gasoline and other consumer goods and is a strategic location for drug traffickers.

As fishermen on the isthmus, the Huave community has strong connections with the cosmogonies of the sea and their lives are tied to the cycles of nature and the earth, as well as of the sea. Aragón alludes to notions of renovation and the region’s cyclical time through texts by Andrés Henestrosa (The Man Dispersed by the Dance, 1929), a Zapotec writer who compiled many of their oral legends for posterity.

Nevertheless, as the video makes clear, Huave identity is undergoing a transformation. Evangelical Christianity has a growing presence in the region and the will of God is used to explain natural disasters, giving a Biblical character to events, one that is intertwined with indigenous beliefs.

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect emphasizes the notion of belonging and rootedness in a place and the connection of the community with its surrounding environment. Aragón underscores the importance of the balance with nature and the way in which progress has undermined the development of the community and the future of generations to come. As Bruno Latour has argued, we must rethink the implications of modernization in terms of ecology and sustainability: “The climate question is a matter of war and peace and for thirty years now, it has been structuring all aspects of geopolitics.”[2] Given the failures of a society in conflict, the challenge is to live on Earth without becoming a cannibal society, predators of our own species.

Virginia Roy

1] Jorge Luis Capdepont Ballina, “Mesoamérica o el Proyecto Mesoamérica: la historia como pretexto,” Revista Liminar. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos, Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, vol. VIII, no. 2, December 2010.

[2] Bruno Laotur and Camille Riquer, “For a Terrestrial Politics,” Eurozine, 2018, available at: https://www.eurozine.com/terrestrial-politics-interview-bruno-latour/.

A Conversation Between Edgardo Aragón and Heidi Ballet

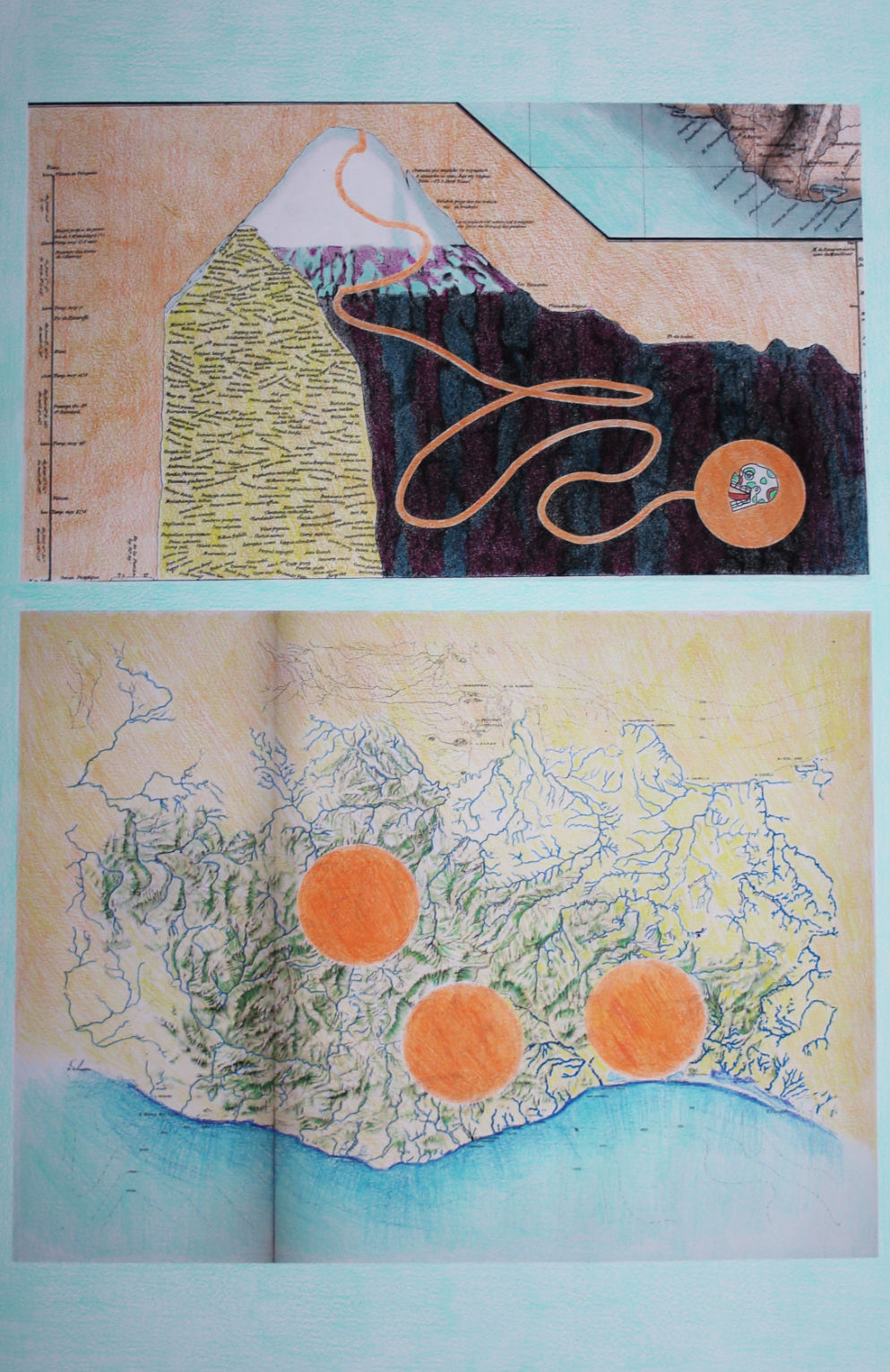

Heidi Ballet (HB): Your new work Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect has been commissioned by Jeu de Paume as part of the exhibition series Our Ocean Your Horizon, which elaborates on the idea of an identity that is based on unfixed grounds. In your work, you concentrate on the area of the ancient civilization of Mesoamerica and offer a reading of the different layers of power lines that are implicitly present in all maps.

Edgardo Aragon (EA): There is on the one hand the new video and on the other hand the maps, which I see as an important part of the work. [...]

COMPLETE CONVERSATION HERE

Other Cartographies to Understand Mesoamerica

Edgardo Aragón Maps

Edgardo Aragón, Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, 2015

Video, 15’

A production of the Jeu de Paume and the CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

Edgardo Aragón

(Oaxaca, 1985; lives and works between Oaxaca and Mexico City, Mexico)

In the work of Edgardo Aragón, the structures of power, violence and politics are addressed in recorded performances that are recreations of past events, freely mixing story lines from family and political history. His work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at various institutions including MACO, Oaxaca (2017); the CAPC, Bordeaux, France (2016); Jeu de Paume, Paris, France (2016); Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Mexico City, Mexico (2012); MoMA P.S.1, New York USA (2012); and the Luckman Gallery, Los Angeles, USA (2012). Group exhibitions where his work has been included have taken place in institutions such as the Renaissance Society in Chicago, USA (2018); Jewish Museum, New York, USA (2015); Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France (2012 and 2011); San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, USA (2011); Laboral Centro de Arte, Gijon, Spain (2011); Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Belgium (2010). His work has also been featured in the 3rd Moscow Biennial of Young Artists, Russia; the 12th Istanbul Biennial, Turkey, and the 8th Mercosul Biennial, Brazil, among others.