Few diseases in the history of humanity have stirred the imaginations of individuals and societies to the extent of aids. The images with which it has been represented have been multiple, varied and of discordant meanings. A cursed word for many, unpronounceable for others, aids has also inspired artistic and cultural creation. The dissemination of images of bodies afflicted by the epidemic instilled panic amongst the population, but also drove many others to compassion and anger. No other illness has sparked such a profusion of images and artistic expressions. It has been a theme of pictorial and photographic works, films and documentaries, drawings and engravings, poetry and prose, plays and testimonial narratives, choreographies and performances and symphonies, rumbas and even cumbias. This has been the case because the epidemic’s impact has gone far beyond its medical consequences, into the realms of society and culture. With its connotations of transgressive sexuality, contaminated blood and death, aids has provoked negative reactions that disrupted personal relationships and social interactions through the fear, rejection and moral condemnation of those affected. In a globalized world, the virus of fear spread at a faster rate than the aids virus itself. However, the epidemic also inspired rage, solidarity and commitment, from which there emerged humanistic responses and organized resistance. As the French philosopher Albert Camus expressed so well in his novel The Plague, epidemics bring with them the most malicious aspects of humanity, but also its greatest virtues.

Today, aids is a term that is on its way out. It is no longer the terrible death sentence it was in the epidemic’s years of terror. Aids = Death was the formula symbolically tattooed on diseased bodies. The stigma of a highly contagious illness led to the mistreatment of those afflicted by the epidemic. Fortunately, this ominous equation no longer corresponds to reality. Imminent death has disappeared from the horizon of many of those who are HIV-positive. The development of increasingly effective and less toxic medications has managed to counteract the pernicious effects of the virus on the organism. Those infected are able to recover their health or at least prevent the disease from advancing to the aids stage. If, at the beginning of the epidemic, the lifespan of those diagnosed as positive was counted in months, their survival has now been extended for decades. HIV infection has become a chronic condition. Though still incurable, it is no longer necessarily fatal. As with any serious illness, it depends on whether the person is diagnosed soon after infection or after the disease has had time to advance. The reversible condition of aids has even driven the United Nations to set the goal of eradicating it by 2030.

But it was necessary to politicize aids in order to achieve the scientific and technological advances that gave patients their dignity back. For the first time—a notable historical novelty—we saw the political mobilization of sick people and the communities that had been hit hardest by the epidemic. In order to access effective treatments, which were extremely expensive, it was necessary to stop traffic on major avenues, collapse on the ground in public spaces (evoking those who had fallen for lack of medical care), threaten to spill infected blood when denied treatment and sue the proper authorities. All this while their time was running out. In the end, they forced health institutions to assume responsibility for providing specialized treatments, free of charge. To date, around 145 000 people are undergoing antiretroviral treatment in Mexico, although it is estimated that the total number of people with HIV is between 200 and 240 000: one third of those infected go untreated, either because they have not been tested or because, despite being aware of their status, they have decided not to undergo treatment for whatever reason.

For the many protests and mobilizations they led, social activists manifested a great sense of imagination in the outreach material they designed. They didn’t hesitate to turn to artistic techniques such as performance or action art to express their demands and discontent. Polo Gómez of Condomóvil is one of the most prominent examples of this: a widely-disseminated image of one of his many interventions shows him climbing the fence protecting the Health Secretariat with his arms extended in an evocation of the crucifixion of Christ, a crown of needles filled with bright red liquid on his head and his bare chest painted with the words “HIV/AIDS NATIONAL EMERGENCY.” Cultural activists also showed off their inventiveness in the nocturnal Marches of Silence held on Mexico City’s main thoroughfares each year in memory of those who had succumbed to aids; in the Wakes for aids Victims held in a variety of public spaces, including some art galleries, in the first days of November; in the One Hundred Artists Against aids festivals held at different cultural centers in the nation’s capital, which featured works addressing the epidemic that were sold to raise funds and in the benefit concerts that brought together a varied constellation of singers, bands and other musicians, such as the one at the Auditorio Nacional featuring Eugenia León, Tania Libertad, Margie Bermejo and Betsy Pecanins. Theater and film were utilized pedagogically, informing and educating the population and encouraging empathy towards those affected by aids. One example of this can be seen in the documentaries made by Maricarmen de Lara. Here, though, we must also mention the attempts by conservative groups, right-wing politicians and religious leaders to use the tragedy of aids to moralize society. This was the case of the preacher and filmmaker Paco del Toro, who used a distorted image of what it means to live with HIV to argue that aids was a divine punishment.

And it is precisely against these distorted images that many people with HIV decided to face the epidemic head-on; the stigma that still weighs on them is one of the primary obstacles to bringing it under control. The taint of the cursed, shameful disease, imposed in the early years of the epidemic, has not been entirely dissipated. The force of this stigma is such that it has managed to instill feelings of shame, guilt and fear among those affected by the disease, aggravating the vulnerability in which many of them live, confining them to a life of isolation and making them unable to take action. Today, nobody should die of aids; nevertheless, deaths still occur, due in part to the paralyzing power of its stigma.

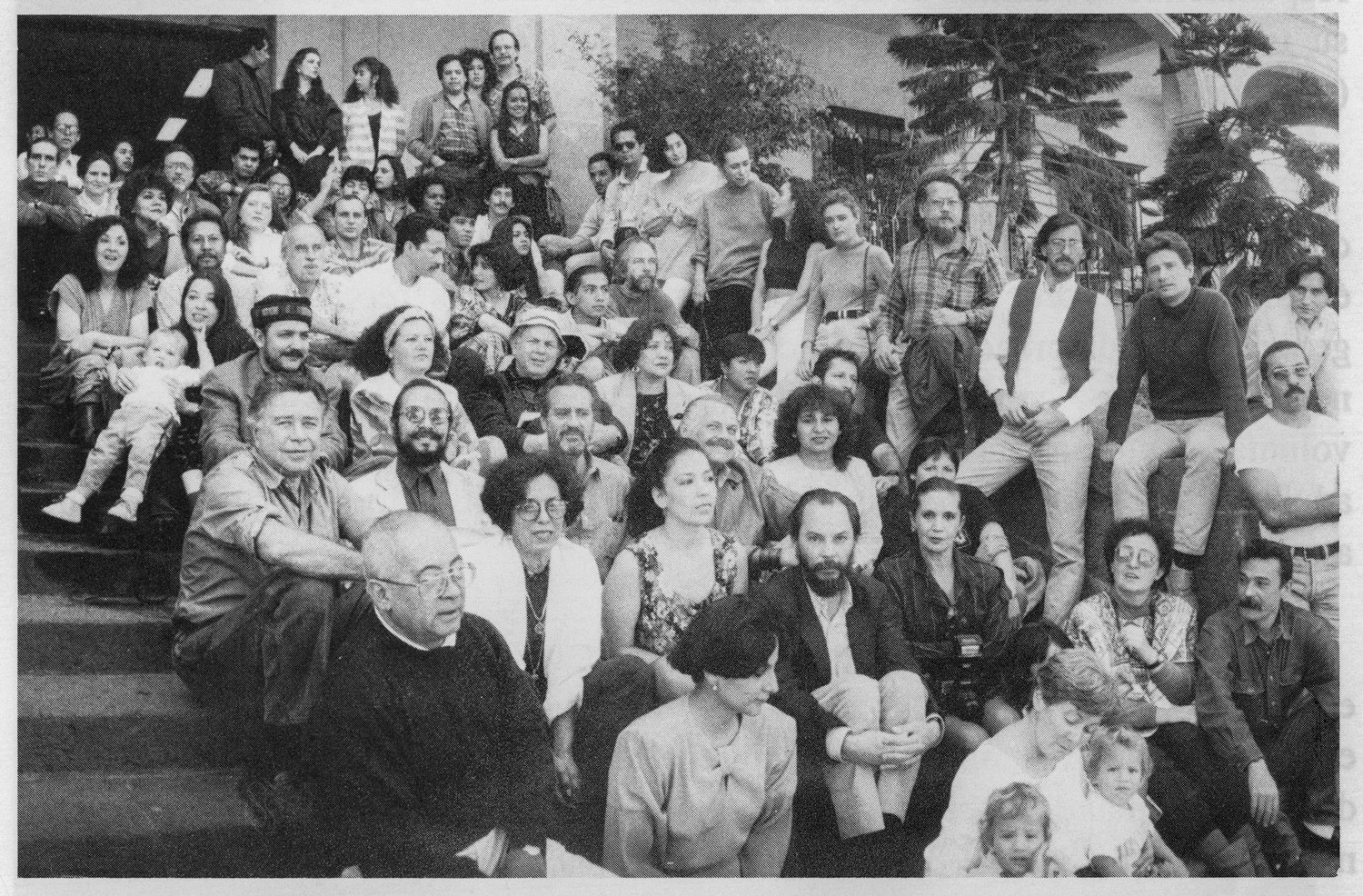

In their determination to shake off imposed identities that slandered them as a threat to public health and thus restore their place as citizens with full rights, many people with HIV decided on a strategy of visibility: they turned to the media to refute malicious lies and fallacies; publicized testimonies of their resilience; showed their faces and life stories in publications and photographic exhibitions such as A Positive Look, organized by Letra S, which was held in a variety of urban spaces, including the Mexico City subway; and participated in many human rights campaigns.

In all of these actions, language was a field in dispute. Understanding that the way of naming illnesses and those they afflict deeply affects people’s perceptions, social and cultural activists worked to deconstruct expressions that served to distort reality: the pernicious association Aids = Death was transformed into Silence = Death, the official epidemiology was corrected by changing the stigmatizing term “at-risk groups” to “risk practices,” the conservative drive to moralize the epidemic found a response in the expression “aids is not a problem of morality, but of public health” and the attempt to blame homosexuals and other marginalized groups was challenged with the slogans “We Are All At Risk” and “A Virus Doesn’t Discriminate.” The incorrect and much-feared term “infection” was also corrected to the more appropriate “transmission.”

Prevention campaigns represented another political and cultural battlefield, a terrain on which to challenge the conservative propaganda issued by politicians and governors, bishops and cardinals, prominent businessmen and fundamentalist groups against condoms, which were called a “health hazard,” a “pollutant,” a “tool of the devil” and other abominations. There were even campaigns by “deniers,” who questioned the existence of HIV and attributed deaths from aids to side effects of the medications used to treat it. Both groups caused a great deal of damage, the first by obstructing prevention campaigns and the second by encouraging patients to stop treatment. There were also voices that promoted punitive actions with the alleged intention of controlling the epidemic, including a marriage ban for HIV-positive individuals in some states, obligatory HIV tests for sex workers as a “health control” measure in several cities and criminal charges for those who transmit the virus, thus making HIV-positive individuals into a potentially criminal class. There are people in prison on precisely these charges.

The history of the fight against aids can be narrated through education and prevention campaigns. While there was an initial, erratic stage that associated HIV with death, sexual promiscuity and marital infidelity, anti-aids activism soon reversed these moralistic messages, playfully asserting the right to pleasure. Many of the pamphlets and educational materials produced with this purpose, which conservatives considered pornographic, abandoned the drive to restrict and discipline sexual behavior in favor of the celebration of a fully realized, risk-free sexuality. It was quickly understood that direct, unambiguous messages were more effective, especially when accompanied by images that spoke more to desire and eroticism than to imperatives. The most explicit of these materials have had to negotiate attempts at censorship.

In this sense, while the HIV pandemic reawakened social prejudices against sexual identities and behaviors that were considered to be “immoral,” it is also true that it sparked a process of social legitimation for these same identities and behaviors. The gay Australian sociologist Dennis Altman has described this paradox as “legitimation through disaster.” The HIV epidemic, largely transmitted via sexual contact, ended up doing away with many sexual taboos. Aids “illuminated the dark labyrinths of human sexuality,” as the HIV specialist Dr. Samuel Ponce de León once said. Like never before, academic research centers scrutinized the sexual behavior of the population. Behavioral surveys investigated the frequency of practices such as oral sex and anal penetration with and without condoms, the number and gender of sexual partners, recreational drug use, sites of sexual encounters, payment for sexual services, etc. The epidemic sparked a broader discussion on sexuality that favored the legitimation of a variety of sexual behaviors and sexual and gender identities and posed the need to change gender norms in order to empower women to make decisions regarding their own bodies and sexuality. The knowledge thus gathered on sexual behavior allowed for a response to the HIV epidemic that had been purged of moralistic prejudices and the drive to persecute patients, instead based only on scientific evidence and a respect for privacy.

The efficacy of antiretroviral therapies has changed the course of the HIV epidemic, changing the lives of thousands of people and allowing them to fully realize themselves. They have even been able to have children free of the fear of transmitting the virus to their offspring. And further still, they are now able to resume their sex lives without guilt. These treatments are capable of reducing the viral load to the point at which the virus is undetectable in standard HIV tests, which means that a person under virologic control is no longer at risk of transmitting the virus, even without condom use. Medications are thus also effective in terms of preventing new infections.

This scientific breakthrough is very liberating for people with HIV. Zero risk for infection has freed them of the stigma of considering themselves to be contagious agents, of the internalized feeling of being a danger to others, by allowing them to resume their sex lives in all their erotic potential. If we allow ourselves to make a comparison, this transformative breakthrough is similar to the liberatory effect of the birth control pill on women’s sexuality.

Undetectable = Untransmittable (U = U) is the new equation that describes the current state of the HIV epidemic and has been adopted by social activists as a battle cry in campaigns for prevention and against stigmas. This formula is the one that inspires the graphic and audiovisual material being currently produced. Together with measures such as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)—which consists of a daily dose of antiretroviral medication for seronegative individuals with a high risk of infection—and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis—the application of antiretrovirals in the hours and days following exposure to the virus—harm reduction measures for people using injectable drugs—such as needle exchange programs—and the use of male and female condoms, we now have an arsenal with which to stop the HIV epidemic.

For it to really work, preventive technology should be designed to respond to the needs and conditions of the sex lives of its users, and not the other way around. Pretending that people should adapt their sexual behavior to one technology or another has never worked. Sexual behavior has shown itself to be more resistant to change than the virus itself has been resistant to the effects of drugs. This is one of the lessons that has been learned over the three-decade course of the epidemic: preventive technology should guarantee the exercise of sexual and reproductive rights. Only a climate of respect for human rights allows for preventive work to flourish and, over the long term, control an epidemic of such medical and social complexity.